The Portrait

This paper is about the history of the portrait of Raoul Wallenberg painted by László Dombrovszky. To the first view the art-historical theme includes specific hidden features.

The painting in course of time emerged from the frames of traditional, European portrait painting. The visage regarding from the human face is the utterance, speaking of the spirit in the body. The artistic portrait is something more than that. It is not simply the representation of the person, the character. According to the Hegelian aesthetics the human figure is the visualization of the ideal by the art.

The image type owns a special one. Its history goes back to the times of the early Orthodox Christian theology and icon painting, to the authentic representation of Christ, to the creation of the first icon that became known in the history of art as the Abgar-Icon. Christ covered his face with a cloth that preserved his face’s lineament. The embodiment of the Word, in the Hegelian sense of the ideal, this certified copy, print cured the sick Abgar King. This image (the first icon) is in contrast to the well established Catholic iconographical image type that is the Veronica’s cloth that depicts the Son of Man of Suffering, preserves the facial image of the Saviour.

Raoul Wallenberg’s portrait painted by Laszlo Dombrovszky in course of time emerged a number of places as an emblematic picture, where from the quiet rescuer’s visage with deep humanism looks at us. The picture got out from its art-history context and quasi had been sacralised. We narrate the history of this sacralised picture originated from the state of a piece of art embedded into everyday’s surrounding of our age. Who are those people to whom we can thank the birth of the only authentic portrait of Wallenberg? How was it painted és what happened to the portrait after finishing it?

This narrative will be some places deficient, we are engaging into assumptions instead of dry facts. Some elements of the history of the picture are lost in the gloom of the dark ages of the past. As the significant proportion of the data of this paper was given by Ninette Dombrovszky, the daughter of the artist, the question rightly arises why we do not know everything about this important piece of art that is elevated into the history of culture, into the collective remembering, rising into the culture of Shoah memory?

In 1944, at the time when the portrait was made the daughter of the painter did not live. She was born long after the war and the artist was already an elderly man. The other important fact is that László Dombrovszky did not really speak about the painting. How is it possible, we could ask? How can it be that someone meets one of the most outstanding men of European humanist ethos of the 20th century history, what is more paints the unique authentic portrait of him and does not speak about it, does not insert it into the narrative of the family?

Gábor Forgács, the son of Vilmos Forgács, who was one of the closest collaborators of Raoul Wallenberg, provides an explanation to this seemingly absurd attitude:

“My father – as Gábor Forgács writes – who died in 1974 and feared his whole life advised me: keep silent, you don’t know anything of Raoul Wallenberg!”1

Those people who were ever in closer contact with Wallenberg were afraid. They feared and remained silent: their lives were in danger.2 In those times an old Bolshevik, once upon a time Minister of Foreign Trade gave Vilmos Forgács a friendly warning that he should keep away himself from the whole theme”.3

When the daughter of László Dombrovszky asked him about Wallenberg she was shushed: “We do not talk about it”. This is the very sentence well known in Hungary because it had been said in many families: people feared for their lives.

Nowadays, when principally one can speak about anything stories turn up out of the blue that were once condemned into silence, we must especially take care to provide authentic narratives. Taking the advantage of the situation created by the free speech and the former falsification of history the revaluation of the past had begun: the relativization of unacceptable sins, the smoothing of the responsibility of sinners in the name of a so-called nuanced historical approach. At the time when we set a commemorative plaque to Raoul Wallenberg in Hungary 2014 the washing away of the responsibility of the Hungarians concerning murdering the Hungarian Jewry was risen to a state political order or level while it is a historical fact that the genocide was committed by the Hungarian authorities besides the indifference of the overwhelming majority of the population and with their active assistance.

We wish to integrate our story into the part of the culture of remembrance however we are aware of the fact that this is only a little slice of the great metanarrative’s social memory. The paper offers previously unknown details from the history to the readers while the most important aspect of this writing is the correspondence with the facts.

The authentic portrait of Raoul Wallenberg – the history of the painting

Vilmos Forgács

The history of the Wallenberg portrait begins with Vilmos Forgács. Who is he? We know him as the closest collaborator of Wallenberg: we can see him on the famous photograph, where Wallenberg sits at his writing desk while a small group of people look at the Swedish diplomat. The man with glasses standing in the middle is Vilmos Forgács. (picture with Wallenberg; portrait)

In a special way the same question is put by András Forgács, the grandson of Vilmos Forgács in his study written about his grandfather: “Who was Vilmos Forgács?” He continues his paper as follows: “after my birth I lived together with my grandparents in the same apartment until 9 years old and at that time I thought that my grandfather was a painter because there were a lot of paintings on the wall. He painted water-colour Cézanne-apples, still-life flower oil-paintings in the style of Frigyes Frank, Balaton-landscapes drawn with crayons in Egry-style, made horse-drawings with charcoal.”4

Vilmos Forgács was born in Budapest, 1896, into a bourgeois family and died in Budapest, 1974. During his life he travelled many times in Belgium, Switzerland, Yugoslavia, Rumania, Czechoslovakia, and the Turkish, English, Swedish, Danish, Polish, Greek, Bulgarian stamps of visa decorate his seven survived passports. Vilmos Forgács was a European citizen.

The young Vilmos Forgács prepared to an artistic career but to the parental advice studied architecture – like Wallenberg. In 1914 military service, after Russian captivity is waiting for him, later he became a red Army soldier in Hungary. He escapes from the White terror of Horthy to Vienna, later to Berlin. After coming home he enters the Kremenecky-Egyesült Izzó-ORION factory where he plays senior positions. He founded in 1935-1936 in Stockholm the Svenska ORION Radio factory by the commission of Lipót Aschner, one of the owners of the ORION and Hugo Wohl, the Chief Executive Officer of the factory.5 Subsequently he owes his life to this Swedish contact. When the Nazi groups occupy Hungary the Gestapo arrested him in 1944 June 2nd. The wife of Forgács asked the help of Per Anger first Embassy Secretary. With the intercession of Per Anger Carl Ivan Danielsson the Swedish ambassador gave to the Forgács family a passport known as Provizoriskt Pass. He was released from the prison as a Swedish citizen and so could leave for a place of refuge already organized before. After these events he became member of Wallenberg’s direct staff.6 He plays an important role in giving the Schutzpasses, in the processing of applications, “he is considered a leading colleague”.7

The location

The “place of refuge” where he moves, the house of Károly Keleti St. Nr.26. is one of the flats of his friend and business partner Rezső Bíró. His son in law is none other than the painter László Dombrovszky who in those days commutes between Zebegény and Budapest, Károly Keleti Street. However his friendship with Vilmos Forgács does not begin this time. Among others Forgács played an important position concerning the exhibitions of the KÚT-society as member of the jury he decided about the painters who could participate in the exhibitions.8 He had good connection with Dombrovszky before the war.9 We do not know whether it was Forgács’s idea to make portrait of Wallenberg, in any case it was Dombrovszky who seemed to be the most appropriate artist for painting it. He spoke well French, with a Russian mother native language, so he could converse using even two languages. He visited Sweden several times and was known as an excellent portraitist. In addition Dombrovszky was trustworthy as he was in close friendly connection with artists who made false papers, distributed leaflets.10 Gábor Forgács the son of Vilmos Forgács said that “it was my father who took Wallenberg to Dombrovszky”.11

In the diary of Wallenberg we see twice the address of Dombrovszky: Keleti Károly Street 26. Once his name, and once his telephone number, too. The first registration is September 22nd 1944, Friday morning 8h15, the second one September 27th, Wednesday 2h Pm. This registration is completed with “Forgacs”, that should refer to Vilmos Forgács12 - yes, surely, as we know that the Forgács family lives in this house provisionally in the flat of his friend, Rezső Bíró on the third floor, while Dombrovszky lived on the fourth floor. At the same time the daughter of Dombrovszky remembers that her father mentioned in relation to the painting that Wallenberg sat three times as a model to the portrait, after he disappeared, did not appear any more …

The event

The fact that there are no documents left neither from Forgács nor stories from Dombrovszky is perhaps the most exciting thing. What exactly happened when Wallenberg sat model to Dombrovszky? Mária Ember the excellent Wallenberg-monographer is also pondering about it in her writing on the history of the painting: “as 9 o’clock Wallenberg had already other thing to do, it is not clear whether they had contacted personally or by telephone or perhaps the painter László Dombrovszky could have made the sketch of the portrait.”13

Oddly enough what we know is the weather, and the consequence that comes from it. This is not indifferent when regarding making a portrait: how will be the lighting conditions? In 1944 September 22 the medium temperature of the day was 13,6 °C, the maximum temperature 18,5 °C, no rain and at the same time the sunshine duration was 3,6 hours, that means in Budapest there was gloomy weather.14 The atelier is on the top of the house, nevertheless in the morning 8h15 am (the Sun rises around 6h30), with a gloomy weather the circumstances are not really ideal to paint the portrait. Anyway Dombrovszky certainly waited his model, so could have made the necessary preparations to the work. Taking into consideration the time for introducing, sitting and setting him into the appropriate pose it must have been enough to such a proficient experienced portraitist as Dombrovszky who could rapidly draw the sketch of the prospective picture. (There are no sketches, no preliminary studies to the portrait that could have remained in the archives of the Dombrovszky family no traces how did the painter think about making the theme, what sort of preliminary idea was used.) According to the memories of the daughter of Dombrovszky her father worked rapidly and in the everyday life he always “drew”: with his eyes, hands he measured the sight surrounding him, he was thinking all the time in images. Sitting in the coffee house he was watching the faces of the people or quickly made crockies, small sketches on a little piece of paper in order to fetch some interesting characters. The painter’s eye is like the photo machine, it seizes the scene in a moment.

The second meeting took place September 27th at 2h afternoon and there is no other programme inscribed to that day in Wallenberg’s diary. This time it will become dark around 18h30’, so – it seems – they have the whole afternoon for painting. The medium temperature of the day was 12,4 °C, the total precipitation of the day was 10,3 mm and there is no sunshine at all. It is early afternoon, a bit raining or the sky is cloudy. Now Wallenberg spends a longer time with Dombrovszky than previously and according to the notebook it is possible that Forgács is also present at the meeting. What are they talking about? Wallenberg, as we know, with a bohemian temperament is not really a strict financier type, like his other family members. Dombrovszky is a pleasant, good conversationalist, good humoured and he was at home in the different artistic saloons. Wallenberg is 32 Dombrovszky 50. Both men, painter and his model, liked arts, women, and society life. Dombrovszky played different musical instruments. Both men travelled a lot, saw the world. What language did they use for the inevitable conversation among such circumstances? Perhaps because of politeness Wallenberg used Russian, the mother language of the painter? Or spoke the elegant French language and from time to time mixed it with some Russian expressions? What could speak about two, Europeans in a flat in Budapest in 1944? The letter written by Forgács in 1945 is the witness to the connection between Wallenberg and Dombrovszky in which he writes referring to this meeting that “you also liked and honoured him”. From this we can draw the conclusion that between the painter and his model a positive emotional contact came about: the sympathy towards the other person is born immediately at the very moment when we catch a glimpse of the worthy person. Naturally it is also possible that instead of or beside the pleasant conversation there were serious, very serious things to be discussed. While Dombrovszky was working on the portrait Wallenberg coordinated the actual tasks to arrange with Forgács. Nevertheless we shall never come to know this. The portrait remained unfinished. We know from Forgács – evidently to help the portrait painting – that there were photos from Wallenberg at Dombrovszky. These pictures were not found. Maybe Wallenberg took with him passport photos or other ones, or perhaps Dombrovszky took a photograph? The painters often use photographs during their work. Just because Wallenberg did not come anymore to the atelier Dombrovszky could finish the portrait. There could have been other reason. In 1944, September 23rd the Soviet troops crossed the Trianon-Hungarian border at Battonya and rapidly advanced ahead. Budapest soon became a front city.

What we do not know either what happened to the painting’s fate after Wallenberg did not come anymore and Dombrovszky left his work unfinished because soon they had to save their lives in the besieged city. From the attacks of the advancing Soviet troops, the bombardments, the artillery attacks they had to move from the Keleti Károly Street, to where later on again were forced to move back and at last survived the liberation from the German occupation. The contradiction of the liberation is soon experienced. Dombrovszky is arrested by the Soviets, he is considered to be a Belorussian as he speaks perfect Russian. His friend Oszkár Papp working in the resistance movement and his brother-in-law András Bíró soon get into prison: Dombrovszky refers to them to confirm his identity. Typically the witnesses are imprisoned, too. Meanwhile Dombrovszky makes friends with the officers who wish the artist to paint their wives’ portraits on the basis of the photographs they have. 15 The portrait of Wallenberg was certainly taken by Vilmos Forgács as in a letter he gladly informs Dombrovszky that the painting was found and it was in the factory (The ORION Radio and Electrical Company), of which Forgács was the Chief manager. Forgács asked to make a copy of the portrait. Making a copy there is no need the personal presence of the model. Forgács writes that he would be very grateful “if now at last the matter of the copy of the painting would come to an understanding”. In the history of painting it is a common phenomenon that a well done picture is made in several copies.

It is clear, should it be by anyone’s idea to make a portrait of Wallenberg, that it was not the result of a simple mood decision. Wallenberg did not ask to make the portrait by passion or hobby. This was a very thought out, deliberate part of a representing, mediatized programme of his activities in Hungary.

Forgács after the first letter the next day (1944, 26th August) urges Dombrovszky in the following letter:

“Dear Stani,

I chase you down for weeks - I repeatedly sent you a message through Baby: in October there will be Wallenberg celebrations in Budapest. They want to unveil his portrait and sculpture. But till then these should be done. Some of his protégées undertook to make it free – his sculpture probably by Pál Pátzay; a photograph is needed to it. As I know you have some pictures of him. Please transmit it to me as soon as possible. Would you please paint again his portrait? Please let me know your answer to it, too. I know that others have much more to thank Wallenberg than you – but I know surely that you also liked and honoured him –

I heartily greet you many times

Vilmos Forgács

Újpest Váci Street 77

Telephone: Újpest 34

“ : 160”

/

The appellation “Stani” (the Hungarian diminutive way of Stanisław) was the privilege of the friends. “Bébi” = “Baby” was the nickname of Dombrovszky’s former wife, Margaret Biro. If he sent a message through his wife that meant that on the one hand Forgács still lived in Keleti Károly Street while on the other hand Dombrovszky worked in the countryside in Zebegény.

The essence of the message was stressed by Forgács with underlining: “Wallenberg”. What is really important for us that he intends to plan the celebrations for October. The letter is written at the end of August, the 26th. In June 21st 1945 the first Wallenberg memorial session is held by the Pest Israelite Jewish Community whereas they put on record that they owe “eternal gratitude” to the Swedish diplomat.16 Compared to this it was only in November the 11th when the Wallenberg Committee was established that acted concerning the sculpture monument of Pátzay. By this time the sculptor had already done the model of the monument. We can see from all these facts that the commemorations concerning Wallenberg were born in the head of Forgács much earlier than the official pursue activities could have begun. We do not know whether Dombrovszky answered him the two letters or not and do not know either why was not done the copy of the portrait. Nevertheless we see that according to the idea of Forgács the sculpture and the painting were playing together, that means he wanted to use the two determinative visual genres of cultural memory at the same time to form the “Wallenberg narrative”. It is worth to mention that provisionally there was a graphical sheet playing a role besides the two dominant genres: the portrait of Wallenberg drawn on a wrapping paper by Pál Forgács, son of Vilmos Forgács, the younger brother of Gábor Forgács (who was also Wallenberg’s protégée). This work served as pattern to the relief-portrait put on the pedestal of the Pátzay sculpture. The sculpture would have been finally inaugurated in the Saint István Park on 10th of April, 1949 but under Soviet pressure the memorial was torn down, taken away, and the relief from the pedestal depicting the profile of Wallenberg is lost forever.

The letter of Forgács has some sensitive details. He mentions even twice once underlining that he wishes Dombrovszky made the copy of the portrait “gratis”, free of charge. We do not have any information whether the painter had received a fee for the portrait or he worked “for free” because of the commitment towards the case. We know that Pátzay got for the sculpture from the Committee down payment and a sum those times considered an impressive honorarium. Directly after the theme of the fee Forgács writes that he knew that others can thank more to Wallenberg than the painter. What did he mean by this? We do not know. Anyway with this he meant that Dombrovszky must not be grateful to Wallenberg, so he could have even asked money for his work. But Forgács immediately adds that “but I surely know that you also liked and honoured him”. The “but” conjunctive means in this case, although you do not owe anything, but as you liked and honoured him, it would be the best if you did not ask honorarium.

We do not know why was not realized the idea, why was not painted the copy. Even the sculpture of Pátzay got from the original plan very hard to its fulfilment and at last more than half a century later, in 1999 April 18th the copy of the original sculpture was put to its place, into the Saint-Stephen Park.

The analysis – interpretation of the picture

The portrait is an oil painting on canvas 80 x 63 cm. It was made according to the traditions of the European civilian portrait representations’ manner: it does not want to serve the painter’s artistic intentions but intending the demands of the customer simply presents the depicted personality to the viewer. At the same time, as all the pieces of art, beyond the mere representation it brings an ethical content, too. We see Wallenberg sitting in front of us, one leg comfortably draped over the other. The whiteness of the head, the face, the shirt’s collar and the white mass of the hands on the knee rise from the dark blur of the picture’s background, the clothes and the suit. The whole painting has a soft, gentle, warm atmosphere. The colours are restrained, they are not contrasting, and they create harmony with each other. Wallenberg looks at us kind-heartedly with his sad eyes a little bit with his head slumped to one side. The curve of his lips is almost womanly soft. As if he gently smiled. As our glimpse runs on the line of the jacket’s lapel to the hand calming on the knee, the peculiar position of the fingers appears. The forefinger and the middle finger are locked together while separated from them the ring finger and the little finger are bent. This is the special position of the hand’s fingers raised to oath, for blessing. A timeless tranquillity is flowing to us from the picture that is discretely nuanced, shaded by the waving of the darker-lighter blurs of the jacket’s plies. The race of the tranquillity and sense of security spreading to us from the painting can be found in its composition. The classical triangle composition originated from the Renaissance creates the stability of the picture.

Why was the painting of Wallenberg made in those times that can be characterized as rampage of madness? Wallenberg apparently turned consciously to the task of representing his activity. He did not leave it to chance to be documented and to present it to the public for the coming future times. (We know that Wallenberg had concrete plans for the reconstructions after the war). They fixed with engineering precision the different activities, coasts, movements of goods, etc. These can be well traced in the so-called Blue Book.17 At the same time Wallenberg took care of the mediatisation of his activities, too.

The historian László Karsai puts the question in one of his lectures why Wallenberg has become so famous, the symbolic figure of Hungary’s rescuer compared, opposite to other rescuers, whose activities were also important but their names are hardly known? The answer can be found in the martyrdom of Wallenberg that he was taken and killed by the henchmen of the Soviet power still up-to-day among unknown circumstances.18 It is indisputable that this ballad gloom favours the creation of myth. At the same time in my estimation an important other factor of being well known is that Wallenberg consciously documented and mediatised his activity: he contracted a professional photographer, namely Tamás Veres who accompanied him even to the terrain.19 If we examine the professional photographs of Veres we can see that these were taken in the manner of propaganda pictures. Their goal was, even if one of them, that beyond the presenting of the depicted person or event their ethical message should be underlined. It’s enough to take a look at the one of the most known photographs. The very one where Wallenberg is sitting on the right side of the picture behind his desk and opposite to him on the other side of the writing desk his most faithful collaborators are standing as if waiting for Wallenberg’s instructions. The picture was composed by the photographer with a great care like a painter while he wishes to give us the impression as if it was “a moment stolen from life”. The conscious, attentive composition is proved, verified by another, less known version of the photograph made some minutes earlier where the people are situated a bit differently as on the one that had become iconic. On the pre-study version Wallenberg looks at his collaborators consequently and his face is not totally in profile. His right hand bends inward a bit, as if he were writing, while on the other photograph he is extending forward and by this the contour of the figure becomes clear and the composition pure. The picture evokes the mood of those sacred images where the Master is seen in the circle of the Disciples, the “Synoptic”.

Dombrovszky’s portrait should fit into this Wallenberg-mythology concept. With the difference between the two genres, photography and oil painting in the convention of the social judgement, opinion: the photography (in this case) first of all is a so-called document while the painting belongs to a more elevated category of a work of art. We have to say that the idea that Wallenberg during the Shoah while saving people even for such less important case devoted and “had time” to sit as a model in a less baleful period is not relevant. Wallenberg and his direct staff members consciously built up the image of the humanist rescuer because they knew that it was not enough to save people from death but it was important to show the exemplary behaviour to the society, too.

The Wallenberg-mythology created its constant attributives: Wallenberg is considered as “legendary personality”, “hero”, “the greatest figure of the Second World War” who is called the “Knight of Humanity”, “Moses from the North” or simply “Saviour of the Jews” or “rescuer”. These epic markers truly reflect the image that came about around Wallenberg. We would like to nuance this heroized attitude and if we absolutely have to characterize Wallenberg we could feel free to use the “man of culture” (homo culturalis) marker in connection with the Swedish diplomat.

What is the portrait about – the ethical subject of the painting

The architectonics of the aesthetical object and the aesthetical content create an organic whole in the work of art that can be artificially separated from each other only during the analysis. Let us do this separation work and ask the question: what is the Wallenberg-portrait painted by Laszlo Dombrovszky about?

The idealization that is observable in the painting is not the reflection of the sympathy between the artist and his model. We can read in Hegel’s Aesthetics, left us from the Dombrovszky’s library, about the nature of portraiture that the art is flattery because it drops away everything what reflects the only-nature sort of mere existence in the phenomenon standing before the painter in order to show or visualize the ideal. The portrait – in essence – does not depict the body, the face, the physiognomy. It is the utterance of the free spirit in its “inner immensity” (Hegel). The history, as Imre Kertész writes, makes one impersonal, fateless. Wallenberg, as the “hero” of the Shoah became a historical figure. However Wallenberg was not swept away by the history. It was Wallenberg who chose the role, the role of saviour that made him a hero in the eyes of the people. Wallenberg’s fate is fulfilled in the hero’s role. At the same time he loses himself as person in this role. He loses even his life. Wallenberg is no more a man. He is already a hero, an icon.20

The portrait of Dombrovszky reflects a complex, contradictory situation. On the one hand it fits into the world of the developed imaginary of the rescuer by raising the model to a different, higher region from the everyday. On the other hand it is sticking out from the heroized Wallenberg-iconography concept that shows an active, doer hero struggling against massacre. In the portrait of Dombrovszky he does not wear upturned-collar coat that is blown by the wind, there is no hat, the suitcase is missing, does not phone, does not sign any “schutzpass” and does not provide his arms to saving his protégées. At Dombrovszky Wallenberg is sitting on a chair, his legs are comfortably crossed, his soothing hand on his knee. He is sitting and does not do anything. He looks at us. A sympathetic man is looking at us from the picture. We do not see anywhere the martyr and the hero of the holocaust, rescuer of thousands of Jews. Is the picture deheroized? We know it is far from Dombrovszky the heroized attitude, in such a way that he even does not act against it. He does not deal with this matter. Wallenberg could have stayed calmly at home in Sweden, could have lived his peaceful, civilian life. Nevertheless he came to Budapest by his own free will because he considered unacceptable what was happening in this city. Those who live here, the majority of the people idly watched that was inadmissible according to their own Christian moral norms, one part of them took part actively in the massacre. The lack of pathos, Wallenberg’s tame, quiet somewhat sad visage, the everyday simplicity with which he appears on the picture shows the necessity of the personal responsibility. There is no need for heroes who do well instead of the average person but it is important that each man according to ability should do what is necessary in the given situation. The fact that Dombrovszky does not show Wallenberg as a hero, but presents him to the viewer without any pathos as an average young man, the artist draws our attention to the personal responsibility of the so-called everyday-people, to the liability that cannot be devolved to any other person, to a hero.

The works of the Wallenberg-memorial sculptures are pieces of phantasy mostly they are imbued with the heroized, romantic aspect of the 19th Century: these are monuments of the loss of persons. A mythical figure is placed instead of the real person. Dombrovszky’s portrait of Wallenberg brings back to us the lost personality in the hero’s role. The artist with the personal, direct, intimate contact with his model reveals by the portrait the everyday life. In this everyday directness presented to us the current viewer can recognize himself. The sacred figure of the “holocaust hero” is replaced by the simple, weekday-man’s immediacy. Thereby all the facts what Wallenberg had done do not anymore belong to the sacred sphere of the heroes saturated with pathos but to the natural, everyday evidences of “anybody”, “whoever”. Our freedom is rooted in our free will: in our responsibility manifesting in everyday life that cannot be devolved into the arisen, exalted remote world of the heroes.

From portrait to icon

The unique authentic portrait of Raoul Wallenberg painted by László Dombrovszky in the course of time exceeded from the frames of European images and became in a certain sense a sacred image, an icon. It lives its life as an organic part of the Wallenberg-memory-culture.

It is obvious that the painting of Dombrovszky was inherently ordered by Vilmos Forgács with the intention of becoming a future Wallenberg-cult icon. Immediately after the war most probably it was Forgács who transmitted the portrait through adventurous roads to Stockholm. At that time in Hungary it was thought that Wallenberg left for Sweden. The painting was donated to the Swedish Royal Portrait Gallery in Gripsholm, near Stockholm by Maj von Dardel, the mother of Raoul Wallenberg. Today the portrait is exhibited at the permanent exhibition of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington.21

Maj Wising, the mother of Raoul Wallenberg around 1970 through an intermediary inquired about the artist who painted the portrait of her son. A certain László Pándy chemical engineer asked Dombrovszky in a letter to meet him. As he wrote Maj Wising asked his brother Kálmán Pándy (who was living in Stockholm) about the painter.22 We do not know anything whether they met or not. The letter was found in the bequest of the artist.

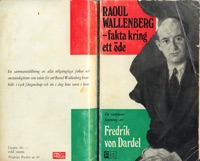

Even László Dombrovszky, the painter of the portrait did not know anything about the fate of the picture. He was surprised when suddenly he got a letter from Stockholm from Steffan Rosén a journalist who attached a press cutting. From this article he was informed that his son Sztanislav had a successful exhibition in Stockholm, in the Bengtsson Gallery. In this context his old father (75) came into play still working to whom Wallenberg sat model during the war in Budapest. The author wrote in the attached article that the portrait was presented by Maj von Dardel to the Gripsholm Gallery and that the young Sztaniszlav met the first time in his life with the portrait on the cover page of the book of Fredrik von Dardel: Raoul Wallenberg-fakta kring ett öde. According to the family-legend the elderly master exclaimed: “Well, it turned up out of the blue!” when he got the letter. According to the statement of the journalist “there were many people who had seen your portrait on Wallenberg and they liked it”. At the same time the author got the information that it was Dombrovszky who offered Wallenberg to sit as a model and that the portrait got to Debrecen and was saved from Hungary via the help of the Swedish Embassy. Dombrovszky in his answer asked Rosén the journalist if possible, to send a copy of the book of Fredrik von Dardel. This had been done and the family still guards the book.

The first Wallenberg-exhibition in Budapest was organized in 1992. An oil-print was made of the original painting considered to be authentic by its size and was exposed at the entrance of the exhibition.23 With this action the original idea of Forgács was quasi realized: the portrait became an emblematic icon of the Hungarian Wallenberg-commemorations. The curator of the exhibition Emil Horn gave this picture at the request of the family to Kitty Kozma-Dombrovszky, the wife who he married after the war.24 (Correspondence of Kitty; an interior of a Budapest home)

- Forgács Gábor, Emlék és valóság, Mindennapjaim Raoul Wallenberggel, Wallenberg Füzetek III., Kolor Optika Nyomda és Kiadó, Budapest, 2006. ↩

- The case of Károly Szabó is very characteristic to that epoch who was also a close colleague of Wallenberg. Szabó became one of the accused of the so-called anti-Zionist conceptual-trial in 1953 and it was only the death of Stalin that he was saved from the fatal judgement. Károly Szabó kept mum was so deeply silent about his activities during the Shoah that even his son Tamás Szabó learned about these from others. Károly Szabó was awarded as Righteous man among nations in 2012 by Yad Vashem. http://mek.oszk.hu/09400/09414/pdf/tortenelmi2.pdf ↩

- Forgács Gábor, Emlék és valóság, Mindennapjaim Raoul Wallenberggel, Wallenberg Füzetek III., Kolor Optika Nyomda és Kiadó, Budapest, 2006., p. 7. The son of Gábor Forgács, grandson of Vilmos Forgács writes the following about the consequences of being silent: “when my grandfather died at the age of 78 and some months later when I first stepped into his room I found a book on the shelf from Jenő Lévai, where I read that the Forgács family first got Swedish citizenship in 1944 and there was a photograph from 1944 where Wallenberg and his closest staff was photographed. But how did my grandfather get to this photo? And who was Wallenberg, before I have never heard about this name.”, András Forgács, Who was Vilmos Forgács, note, 2014. ↩

- András Forgács, Who was Vilmos Forgács, note, 2014. ↩

- Forgács Gábor, Emlék és valóság, Mindennapjaim Raoul Wallenberggel, Wallenberg Füzetek III., Kolor Optika Nyomda és Kiadó, Budapest, 2006, p.21.,photo and p. 46. ↩

- Forgács Gábor, Emlék és valóság, Mindennapjaim Raoul Wallenberggel, Wallenberg Füzetek III., Kolor Optika Nyomda és Kiadó, Budapest, 2006, p. 22.,p. 70., p. 74. ↩

- Forgács Gábor, Emlék és valóság, Mindennapjaim Raoul Wallenberggel, Wallenberg Füzetek III., Kolor Optika Nyomda és Kiadó, Budapest, 2006, p.77., pp. 79-80. ↩

- KÚT: (New Society of Visual Artists) Active in Budapest (1924-1949) as a progressive, French-styled artists’ society with the leadership of the painter Ödön Márffy (1878-1959). ↩

- Telephone interview of Dr. Ninette Dombrovszky, art historian, with Gábor Forgács November 25th 2012 concerning the Commemorative plaque project. ↩

- Friends of Dombrovszky –Oszkár Papp (Japi), István Szőnyi, Robert Berény –belonged to the Muharay-Group and the Gresham-Circle taking part in the resistance ↩

- Telephone interview of Dr. Ninette Dombrovszky art historian with Gábor Forgács November 25th 2012 in connection with the Commemorative plaque project. ↩

- Ember Mária, Egy ismeretlen Wallenberg-portré története, Köztársaság, 1992, 7 ↩

- Ember Mária, Egy ismeretlen Wallenberg-portré története, Köztársaság, 1992, 7 ↩

- On the basis of the data of the National Weather Service ↩

- András Bíró, Hazajöttem, L’Harmattan, 2006; and Ninette Dombrovszky’s interview with the painter Oszkár Papp 2005, 2006, 2008 ↩

- Ember Mária, Wallenberg Budapesten, Városháza, Budapest, 2000, p. 186. ↩

- Forgács Gábor, Emlék és valóság, Mindennapjaim Raoul Wallenberggel, Wallenberg Füzetek III., Kolor Optika Nyomda és Kiadó, Budapest, 2006.,p.10. ↩

- 2012.05.30. Lecture of László Karsai: Raoul Wallenberg’s companions and enemies, 477 Visualizzazioni - Caricato il 23/06/2012 ↩

- http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/media_oi.php?MediaId=1226 ↩

- In a project students of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem on the basis of Wallenberg photographs tried to create their own, personal Wallenberg portraits dissolving the tension between the everyday, simple man and the iconic hero. Portraits of Raoul Wallenberg Workshop and Exhibition by Bezalel Students, The Swedish Embassy and Bezalel Academy Israel, 2014. ↩

- http://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1092972 ↩

- Calman de Pándy 1908-1988 translator and simultaneous translator member of the Swedish Writers Union and the National Press Club ↩

- Wallenberg-exhibition, Budapest, Legújabb Kori Történeti Múzeum, (New-Age Historical Museum), August 4th 1992-October 31st. ↩

- Kitty Kozma-Dombrovszky the wife of Dombrovszky (also persecuted by the Shoah) followed the fate of the painting. She diligently collected the different publications about Wallenberg and the portrait. When she got to Sweden out of her work she wished to visit the Gripsholm Castle to see her husband’s work. She corresponded with the curator of the Museum but unfortunately at that very moment the picture was borrowed to the Washington Holocaust Museum. She preserved the copy of the painting presented from the 1992 Budapest Wallenberg-exhibition on the wall of her room among the other Dombrovszky paintings. (pics) ↩